Lec3

1. Preparation: Operating system organization¶

1. book-riscv-rev3 Chapter2

2. xv6 code: kernel/proc.h, kernel/defs.h, kernel/entry.S, kernel/main.c, user/initcode.S, user/init.c, and skim kernel/proc.c and kernel/exec.c

- A key requirement for an operating system is to support several activities at once.

- an operating system must fulfill three requirements: multiplexing, isolation, and interaction.

1.1 Abstracting physical resources¶

- That is, one could implement the system calls in Figure 1.2 as a library, with which applications link. In this plan, each application could even have its own library tailored to its needs. Applications could directly interact with hardware resources and use those resources in the best way for the application

- It’s more typical for applications to not trust each other, and to have bugs, so one often wants stronger isolation than a cooperative scheme provides.

- To achieve strong isolation it’s helpful to forbid applications from directly accessing sensitive hardware resources, and instead to abstract the resources into services.

- Similarly, Unix transparently switches hardware CPUs among processes, saving and restor- ing register state as necessary, so that applications don’t have to be aware of time sharing.

- Many forms of interaction among Unix processes occur via file descriptors. Not only do file descriptors abstract away many details (e.g., where data in a pipe or file is stored), they are also defined in a way that simplifies interaction.

1.2 User mode, supervisor mode, and system calls¶

- Instead, the operating system should be able to clean up the failed application and continue running other applications. To achieve strong isolation, the operating system must arrange that applications cannot modify (or even read) the operating system’s data structures and instructions and that applications cannot access other processes’ memory.

- CPUs provide hardware support for strong isolation.

- machine mode, supervisor mode, and user mode

- In supervisor mode the CPU is allowed to execute privileged instructions

- An application can execute only user-mode instructions (e.g., adding numbers, etc.) and is said to be running in user space, while the software in supervisor mode can also execute privileged instructions and is said to be running in kernel space.

- An application that wants to invoke a kernel function (e.g., the read system call in xv6) must transition to the kernel; an application cannot invoke a kernel function directly.

- It is important that the kernel control the entry point for transitions to supervisor mode; if the application could decide the kernel entry point, a malicious application could, for example, enter the kernel at a point where the validation of arguments is skipped.

1.3 Kernel organization¶

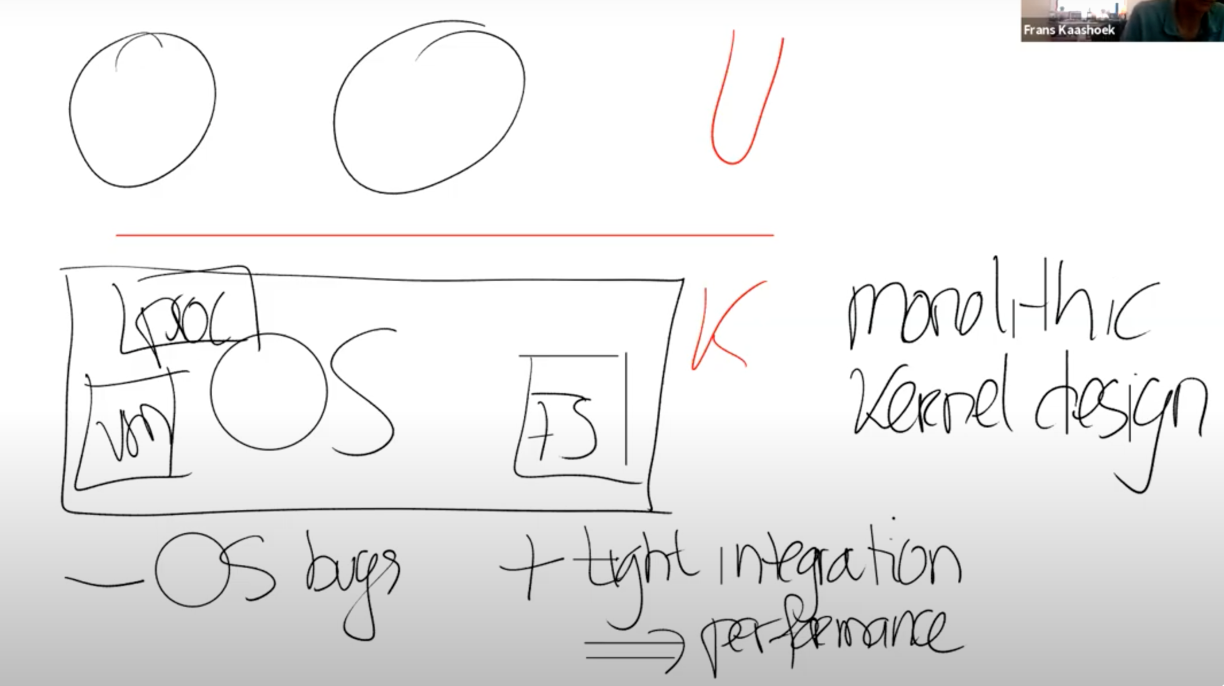

- A key design question is what part of the operating system should run in supervisor mode.

- In this organization the entire operating system runs with full hardware privilege.

- Furthermore, it is easier for different parts of the op- erating system to cooperate.

- A downside of the monolithic organization is that the interfaces between different parts of the operating system are often complex (as we will see in the rest of this text)

- easy for an operating system developer to make a mistake. In a monolithic kernel, a mistake is fatal, because an error in supervisor mode will often cause the kernel to fail.

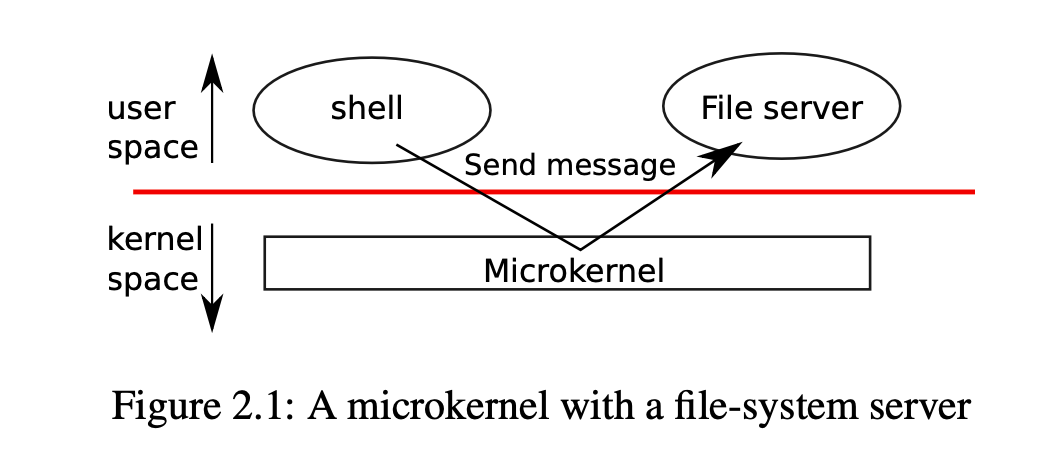

- To reduce the risk of mistakes in the kernel, OS designers can minimize the amount of operating system code that runs in supervisor mode, and execute the bulk of the operating system in user mode. This kernel organization is called a microkernel.

- In a microkernel, the kernel interface consists of a few low-level functions for starting applica- tions, sending messages, accessing device hardware, etc. This organization allows the kernel to be relatively simple, as most of the operating system resides in user-level servers.

- Many Unix kernels are monolithic.

- There is much debate among developers of operating systems about which organization is better, and there is no conclusive evidence one way or the other.

- From this book’s perspective, microkernel and monolithic operating systems share many key ideas. They implement system calls, they use page tables, they handle interrupts, they support processes, they use locks for concurrency control, they implement a file system, etc.

- Xv6 is implemented as a monolithic kernel, like most Unix operating systems.

1.4 Code: xv6 organization¶

- The source is divided into files, following a rough notion of modularity.

1.5 Process overview¶

- The unit of isolation in xv6 (as in other Unix operating systems) is a process. The process ab- straction prevents one process from wrecking or spying on another process’s memory, CPU, file descriptors, etc. It also prevents a process from wrecking the kernel itself, so that a process can’t subvert the kernel’s isolation mechanisms. The kernel must implement the process abstraction with care because a buggy or malicious application may trick the kernel or hardware into doing something bad (e.g., circumventing isolation).

- To help enforce isolation, the process abstraction provides the illusion to a program that it has its own private machine.

- Xv6 uses page tables (which are implemented by hardware) to give each process its own ad- dress space. The RISC-V page table translates (or “maps”) a virtual address (the address that an RISC-V instruction manipulates) to a physical address (an address that the CPU chip sends to main memory).

- Xv6 maintains a separate page table for each process that defines that process’s address space. As illustrated in Figure 2.3, an address space includes the process’s user memory starting at virtual address zero. Instructions come first, followed by global variables, then the stack, and finally a “heap” area (for malloc) that the process can expand as needed.

- the trampoline page contains the code to transition in and out of the kernel and mapping the trapframe is necessary to save/restore the state of the user process

- The xv6 kernel maintains many pieces of state for each

- A process’s most important pieces of kernel state are its page table, its kernel stack, and its run state.

- Each process has a thread of execution (or thread for short) that executes the process’s instruc- tions. A thread can be suspended and later resumed. To switch transparently between processes, the kernel suspends the currently running thread and resumes another process’s thread.

- Each process has two stacks: a user stack and a kernel stack (p->kstack).

- while a process is in the kernel, its user stack still contains saved data, but isn’t ac- tively used. A process’s thread alternates between actively using its user stack and its kernel stack. The kernel stack is separate (and protected from user code) so that the kernel can execute even if a process has wrecked its user stack.

- A process can make a system call by executing the RISC-V ecall instruction. This instruction raises the hardware privilege level and changes the program counter to a kernel-defined entry point.

- A process’s thread can “block” in the kernel to wait for I/O, and resume where it left off when the I/O has finished.

- A process’s page table also serves as the record of the addresses of the physical pages allocated to store the process’s memory.

- In summary, a process bundles two design ideas: an address space to give a process the illusion of its own memory, and, a thread, to give the process the illusion of its own CPU. In xv6, a process consists of one address space and one thread. In real operating systems a process may have more than one thread to take advantage of multiple CPUs. process

1.6 Code: starting xv6, the first process and system call¶

- The RISC-V starts with paging hardware disabled: virtual addresses map directly to physical addresses.

- The reason it places the kernel at 0x80000000 rather than 0x0 is because the address range 0x0:0x80000000 contains I/O devices.

- The code at _entry loads the stack pointer register sp with the address stack0+4096, the top of the stack, because the stack on RISC-V grows down.

- The function start performs some configuration that is only allowed in machine mode, and then switches to supervisor mode.

- Before jumping into supervisor mode, start performs one more task: it programs the clock chip to generate timer interrupts.

- Once the kernel has completed exec, it returns to user space in the /init process.

1.7 Security Model¶

- Here’s a high-level view of typical security assumptions and goals in operating system design.

- The operating system must assume that a process’s user-level code will do its best to wreck the kernel or other processes.

- The kernel’s goal to restrict each user processes so that all it can do is read/write/execute its own user memory

- The kernel must prevent any other actions. This is typically an absolute requirement in kernel design.

- The expectations for the kernel’s own code are quite different. Kernel code is assumed to be written by well-meaning and careful programmers. Kernel code is expected to be bug-free, and certainly to contain nothing malicious. This assumption affects how we analyze kernel code.

- It’s difficult to prevent clever user code from making a system unusable (or causing it to panic) by consuming kernel-protected resources – disk space, CPU time, process table slots, etc.

- It’s worthwhile to design safeguards into the kernel against the possibility that it has bugs: assertions, type checking, stack guard pages, etc.

- Finally, the dis- tinction between user and kernel code is sometimes blurred

1.8 Real World¶

- Most operating systems have adopted the process concept, and most processes look similar to xv6’s.

- Modern operating systems, however, support several threads within a process, to allow a single process to exploit multiple CPUs.

2. Lecture 3¶

1. Lecture Topic:

- OS design

- system calls

- micro/monolithic kernel

- First system call in xv6

2. Goal of OS

- run multiple applications

- isolate them

- multiplex them

- share

2.1 Isolation¶

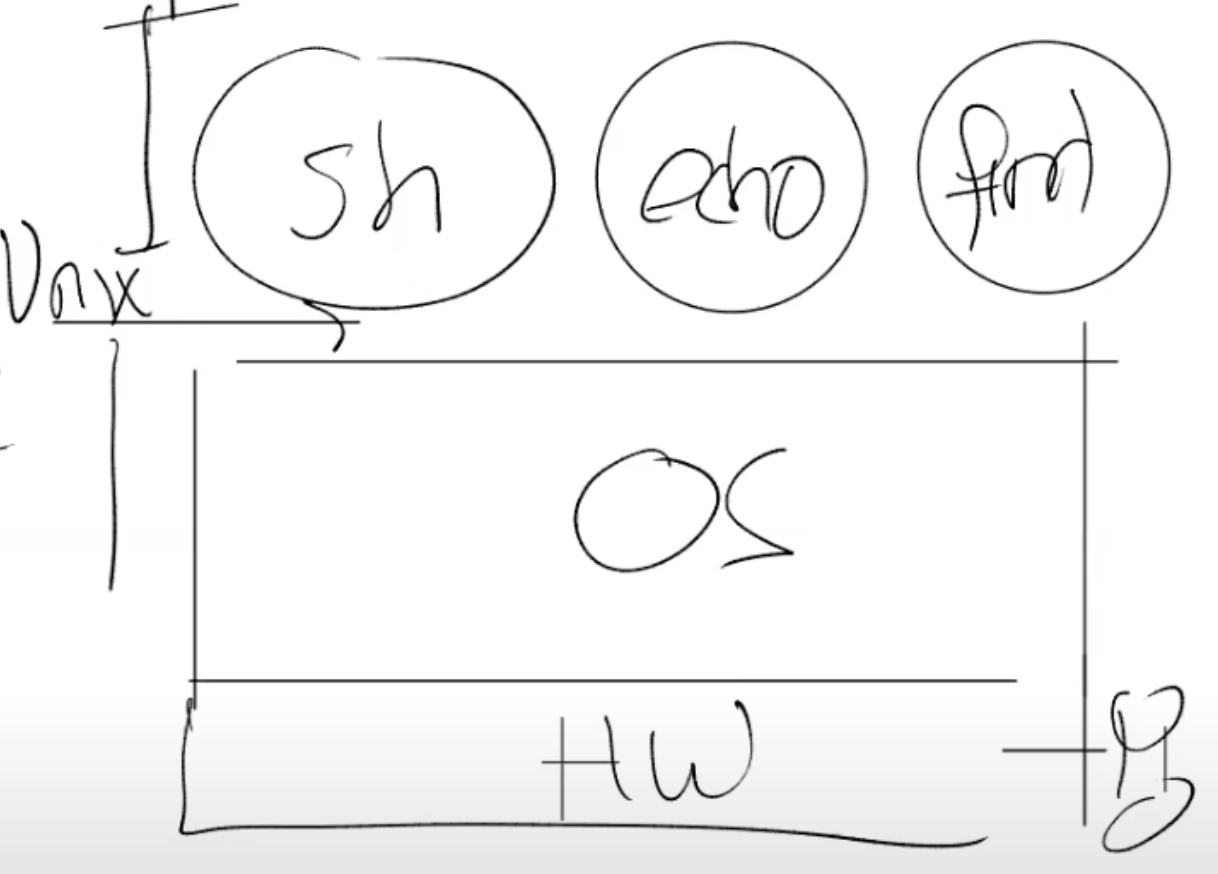

1. Strawman design: No OS

- Application directly interacts with hardware

- CPU cores & registers

- DRAM chips

- Disk blocks

- ...

- OS library perhaps abstracts some of it

2. Strawman design: not conducive to multiplexing

- each app periodically must give up hardware

- BUT, weak isolation

- app forgets to give up, no other app runs

- apps has end-less loop, no other app runs

- you cannot even kill the badly app from another app

- but used by real-time OSes

- "cooperative scheduling"

3. Strawman design: not conducive to memory isolation

- all apps share physical memory

- one app can overwrites another apps memory

- one app can overwrite OS library

4. Unix interface conducive to OS goals

- abstracts the hardware in way that achieves goals

- processes (instead of cores): fork

- OS transparently allocates cores to processes

- Saves and restore registers

- Enforces that processes give them up

- Periodically re-allocates cores

- OS transparently allocates cores to processes

- memory (instead of physical memory): exec

- Each process has its "own" memory

- OS can decide where to place app in memory

- OS can enforce isolation between memory of different apps

- OS allows storing image in file system

- files (instead of disk blocks)

- OS can provide convenient names

- OS can allow sharing of files between processes/users

- pipes (instead of shared physical mem)

- OS can stop sender/receiver

2.2 Defensive¶

OS must be defensive

- an application shouldn't be able to crash OS

- an application shouldn't be able to break out of its isolation

- => need strong isolation between apps and OS

- approach: hardware support

- user/kernel mode

- virtual memory

2.3 Hardware support¶

1. Processors provide user/kernel mode

- kernel mode: can execute "privileged" instructions

- e.g., setting kernel/user bit

- e.g., reprogramming timer chip

- user mode: cannot execute privileged instructions

- Run OS in kernel mode, applications in user mode

- RISC-V has also an M mode, which we mostly ignore

2. Processors provide virtual memory

- Hardware provides page tables that translate virtual address to physical

- Define what physical memory an application can access

- OS sets up page tables so that each application can access only its memory

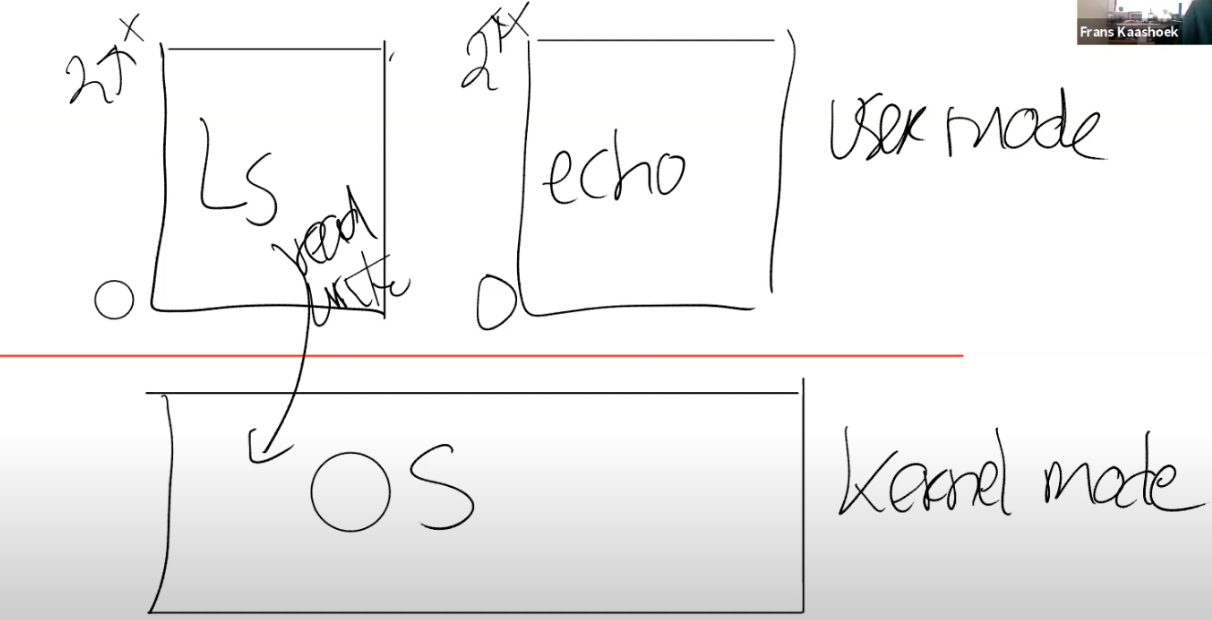

2.4 User/Kernel mode change¶

1. Apps must be able to communicate with kernel

- Write to storage device, which is shared => must be protected => in kernel

- Exit app

- ...

2. Solution: add instruction to change mode in controlled way

- ecall

- enters kernel mode at a pre-agreed entry point

- user / kernel (redline)

- app -> printf() -> write() -> SYSTEM CALL -> sys_write() -> ...

- user-level libraries are app's private business

- kernel internal functions are not callable by user

- other way of drawing picture:

- syscall 1 -> system call stub -> kernel entry -> syscall -> fs

- syscall 2 -> proc

- system call stub executes special instruction to enter kernel

- hardware switches to kernel mode

- but only at an entry point specified by the kernel

- syscall need some way to get at arguments of syscall

2.5 Monolithic Kernel vs Micro Kernel¶

1. Kernel is the Trusted Computing Base (TCB)

- Kernel must be "correct"

- Bugs in kernel could allow user apps to circumvent kernel/user

- Kernel must treat user apps as suspect

- User app may trick kernel to do the wrong thing

- Kernel must check arguments carefully

- Setup user/kernel correctly

- Kernel in charge of separating applications too

- One app may try to read/write another app's memory

- => Requires a security mindset

- Any bug in kernel may be a security exploit

Aside: can one have process isolation WITHOUT h/w-supported

- kernel/user mode and virtual memory?

- yes! use a strongly-typed programming language

- For example, see Singularity O/S

- the compiler is then the trust computing base (TCB)

- but h/w user/kernel mode is the most popular plan

2. Monolothic kernel

- OS runs in kernel space

- Xv6 does this. Linux etc. too.

- kernel interface == system call interface

- one big program with file system, drivers, &c

- good: easy for subsystems to cooperate

- one cache shared by file system and virtual memory

- bad: interactions are complex

- leads to bugs

- no isolation within

3. Microkernel design

- many OS services run as ordinary user programs

- file system in a file server

- kernel implements minimal mechanism to run services in user space

- processes with memory

- inter-process communication (IPC)

- kernel interface != system call interface

- good: more isolation

- bad: may be hard to get good performance

- both monolithic and microkernel designs widely used

4. Xv6 case study

- Monolithic kernel

- Unix system calls == kernel interface

- Source code reflects OS organization (by convention)

- user/ apps in user mode

- kernel/ code in kernel mode

- Kernel has several parts

- kernel/defs.h(proc, fs, ...)

- Goal: read source code and understand it (without consulting book)

2.6 Building kernel¶

1. Using xv6

- Makefile builds

- kernel program

- user programs

- mkfs

- $ make qemu

- runs xv6 on qemu

- emulates a RISC-V computer

2. Building kernel

.c -> gcc -> .s -> .o \ .... ld -> a.out .c -> gcc -> .s -> .o /

- makefile keeps .asm file around for binary

- see for example, kernel/kernel.asm

2.7 RISC-V computer¶

1. The RISC-V computer

- RISC-V processor with 4 cores

- RAM (128 MB)

- support for interrupts (PLIC, CLINT)

- support for UART

- allows xv6 to talk to console

- allows xv6 to read from keyboard

- support for e1000 network card (through PCIe)

2. Development using Qemu

- More convenient than using the real hardware

- Qemu emulates several RISC-V computers

- we use the "virt" one(https://github.com/riscv/riscv-qemu/wiki)

- close to the SiFive board (https://www.sifive.com/boards), but with virtio for disk

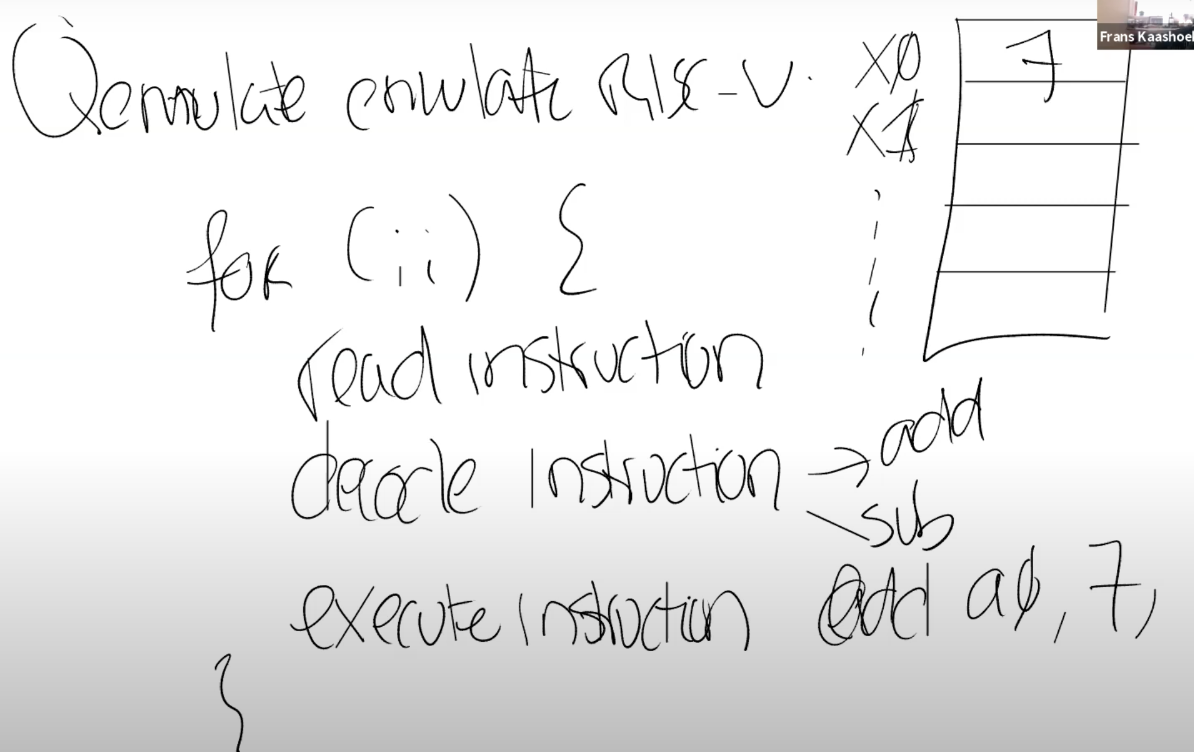

3. What is "to emulate"?

- Qemu is a C program that faithfully implements a RISC-V processor

for (;;) {

read next instructions

decode instruction

execute instruction (updating processor state)

}

software = hardware

2.8 Boot xv6¶

- $ make CPUS=1 qemu-gdb

- runs xv6 under gdb (with 1 core)

- Qemu starts xv6 in kernel/entry.S (see kernel/kernel.ld)

- set breakpoint at _entry

- look at instruction

- info reg

- set breakpoint at main

- Walk through main

- single step into userinit

- Walk through userinit

- show proc.h

- show allocproc()

- show initcode.S/initcode.asm

- break forkret()

- walk to userret

- break syscall

- print num

- syscalls[num]

- exec "/init"

- set breakpoint at _entry